Sunspots and Solar Cycles

Figure

1

The

above chart clearly shows a weakening trend of sunspots in solar

cycles 22, 23 and 24. These are the latest in a sequence dating from

1755, when extensive recording of solar sunspot activity began. Note

that the peak of solar cycle 24, which occurred in 2014, is only

about half that of solar cycle 22, which peaked about 1989. This

portends global cooling—not global warming. Sunspots are dwindling

to lows not seen in 200 years. In 2008, during the solar minimum of

cycle 23, there were 266 days with no sunspots. This is considered a

very deep solar minimum. You can check out pictures of sunspots—or

their absence—day after day for recent years at

http://tinyurl.com/6zck4x.

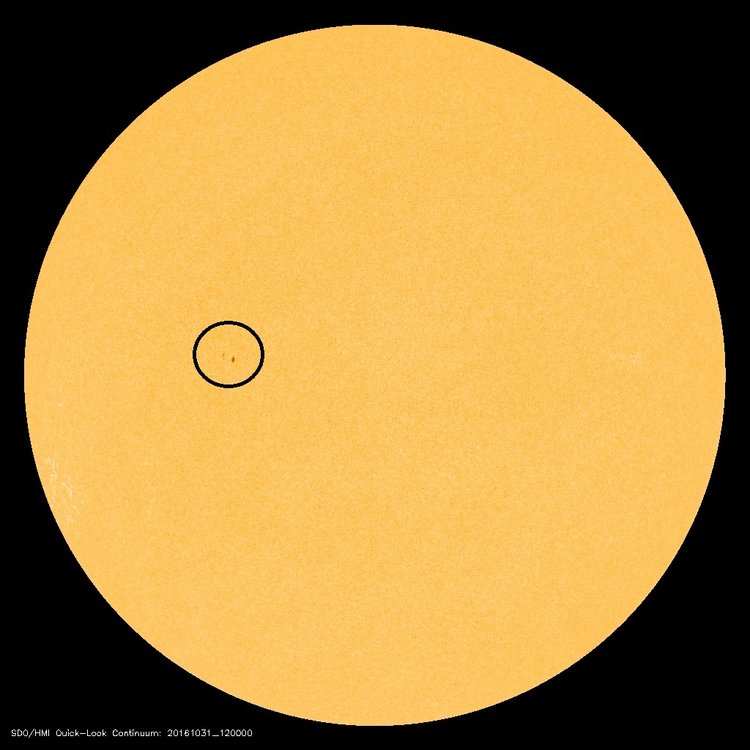

Here is a recent picture of the sun with a single sunspot region as

the sun marches toward a cyclical low expected in 2019 or 2020.

Figure

2

Sunspots

have been observed for millennia, first in China and with a telescope

for the first time by Galileo in 1610. We now have a 400-year record

of sunspot cycle observations, from which we can see a cycle length

of about 11 years. Combining this fact with the discovery of a strong

correlation between solar activity and radioactive carbon 14 in tree

rings, it has been possible to backdate sunspot cycles from the sun's

magnetic cycles for a thousand years, back to the Oort Minimum in the

year 1010.

Sunspots occur when magnetic fields rip through the sun's surface, producing holes in the sun's corona, solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and changes in the solar wind, the stream of charged particles emanating from the sun. The solar wind, by modulating the galactic cosmic rays which reach the earth, determines both the formation of clouds and the carbon dioxide level in the earth's atmosphere—which has nothing to do with emissions from factories or automobiles! This is why in the 15 years prior to 2013, when humans produced 461 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide—compared to only 302 billion tonnes in the preceding 15 years—there was no global warming; in fact, the earth actually cooled despite the massive increase in carbon dioxide emissions. The fear mongers claim a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide will produce catastrophic global warming. But Reid Bryson, founding chairman of the Department of Meteorology at the University of Wisconsin, has stated, “You can go outside and spit and have the same effect as a doubling of carbon dioxide.”

Sunspots occur when magnetic fields rip through the sun's surface, producing holes in the sun's corona, solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and changes in the solar wind, the stream of charged particles emanating from the sun. The solar wind, by modulating the galactic cosmic rays which reach the earth, determines both the formation of clouds and the carbon dioxide level in the earth's atmosphere—which has nothing to do with emissions from factories or automobiles! This is why in the 15 years prior to 2013, when humans produced 461 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide—compared to only 302 billion tonnes in the preceding 15 years—there was no global warming; in fact, the earth actually cooled despite the massive increase in carbon dioxide emissions. The fear mongers claim a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide will produce catastrophic global warming. But Reid Bryson, founding chairman of the Department of Meteorology at the University of Wisconsin, has stated, “You can go outside and spit and have the same effect as a doubling of carbon dioxide.”

After

about 210 years, sunspot cycles “crash” or almost entirely die

out, and the earth can cool dramatically. These unusually cold

periods last several decades. Of greatest concern to us is the

Maunder Minimum, which ran from 1645 to 1715. Figure 3 shows the

paucity of sunspots during this time. Some years had no sunspots at

all. The astronomer Sporer reported only 50 sunspots during a 30-year

period, compared to 40,000 to 50,000 typical for that length of time.

Figure

3

Since

the Maunder Minimum, a less extreme but still significantly

below-average period of cooler temperatures occurred during the

Dalton Minimum (1790 to 1830), also shown on the graph.

At

least as far back as 2007—before Cycle 23 had bottomed—a Russian

solar physicist, predicted what we are seeing now. Professor

Habibullo Abdussamatov, head of the Pulkovo Observatory in Russia,

noting that solar irradiance had already begun to fall, said

a slow decline in temperatures would begin as early as 2012-2015 and

lead to a deep freeze in 2050-2060 that will last about fifty years.

He said the warming we've been witnessing was caused by increased

solar irradiance, not CO2

emissions:

It

is no secret that increased solar irradiance warms Earth's oceans,

which then triggers the

emission of large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere

(italics added.) So the common view that man's industrial activity is

a deciding factor in global warming has emerged from a

misinterpretation of cause and effect relations.

Further,

debunking the very notion of a greenhouse effect, the renowned

scientist said:

Ascribing

'greenhouse' effect properties to the Earth's atmosphere is not

scientifically substantiated. Heated greenhouse gases, which become

lighter as a result of expansion, ascend to the atmosphere only to

give the absorbed heat away.

In

a paper

published in 2009, Abdussamatov wrote that there have been 18

Maunder-type minima of deep temperature drops in the last 7,500

years, “which without fail follow after natural warming.” And,

correspondingly,

while in the periods of high sunspot maxima, there have been periods of global warming. Such changes in the climate of the Earth could be caused only by lasting and significant changes in the Sun, because there was absolutely no industrial effect on nature in those times.

We

would expect the onset of the phase of deep minimum in the present

200-year cycle of cyclic activity of the Sun to occur at the

beginning of solar cycle 27; i.e., tentatively in the year 2042 plus

or minus 11 years, and potentially lasting 45-65 years.

Regarding

analyses of ice cores in Greenland and Antarctica, Abdussamatov

wrote:

It

has been seen that substantial increases in the concentration of

carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and global climate warming have

occurred cyclically, even when there was as yet no industrial action

on nature. It has also been established that periodic, very

substantial increases in the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere

for a period of 420 thousand years never preceded warming,

but, on the contrary, always followed an increase in the temperature

with a delay of 200-800 years, i.e., they were its consequence

(italics and boldface added.)

In

an update in October 2013, Abdussamatov warned,

“We are now on an unavoidable advance towards a deep temperature

drop.”

Abdussamatov's

conclusions about global cooling came from his studies of the sun,

but another scientist came to a similar conclusion by studying ocean

currents. This should not be surprising because, as NASA has stated,

“uneven heating from the sun

drives

the air and ocean

currents

that produce the Earth's climate.” Don Easterbrook, a geology

professor and climate scientist, correctly predicted

back in 2000 that the earth was entering a cooling phase. He made his

prediction by tracing a “consistently recurring pattern” of

alternating warm and cool ocean cycles known as the Pacific Decadal

Oscillation (PDO). He found this cycle recurring every 25 to 30 years

for almost 500 years. Projecting this forward, he concluded “the

PDO said we're due for a change,” and that happened.

Asked

by CNSNews

about the Intergovernment Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Easterbrook

said they “ignored all the data I gave them...every time I say

something about the projection of climate into the future based on

real data, they come out with some [computer] modeled data that says

this is just a temporary pause...I am absolutely dumfounded by the

totally absurd and stupid things said every day by people who are

purportedly scientists that make no sense whatsoever....These people

are simply ignoring real-time data that has been substantiated and

can be replicated and are simply making stuff up....What they're

doing in the U.S. is using CO2 to impose all kinds of restrictions to

push a socialist government.”

Is

it true that the global-warming issue has become a front for a

political ideology? Has it become a tool for increasing government

control over our lives, not just in the U.S. but all over the globe?

In 2010 a leading member of the United Nation's IPCC said, “One has

to free oneself from the illusion that international climate policy

is environmental policy. This has almost nothing to do with

environmental policy anymore.” Now it's not about saving the

environment but about redistributing wealth, said Ottmar Edenhofer,

a co-chair of the IPCC's Working Group III and a lead author of the

IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report (2007). “We redistribute the

world's wealth by climate policy.”

Edenhofer

told a German news outlet (NZZ AM Sonntag

): “Basically, it's a big mistake to discuss climate policy

separately from the major themes of globalization. The climate summit

in Cancun at the end of the month is not a climate conference but one

of the largest economic conferences since the Second World War.”

The

Cancun agreement set up a “Green Climate Fund” to administer

assistance to poor nations suffering from floods and drought due to

global warming. The European Union, Japan and the United States have

led pledges of $100 billion per year for poor nations up to 2020,

plus $30 billion in immediate assistance.

The

IPCC regularly submits its reports to its Expert Reviewers Panel. As

you might expect, most of its appointments to this panel have been

supporters of global warming. A few nonbelievers have been included

to give the appearance of balance, but their comments and questions

have been routinely ignored as the IPCC focuses on what it claims to

be the “consensus” view.

Only

one person has been been on every IPCC Expert Reviewers Panel, dating

back to 1990. That man is Dr. Vincent Gray of New Zealand. He

submitted a very large number of comments to IPCC drafts. Here are

some of his comments from a letter

he wrote on March 9, 2008:

Over the period I

have made an intensive study of the data and procedures used by IPCC

contributors throughout their whole study range....Right from the

beginning I have had difficulty with this procedure. Penetrating

questions often ended without any answer. Comments on the IPCC drafts

were rejected without explanation, and attempts to pursue the matter

were frustrated indefinitely....

I

have been forced to the conclusion that for significant parts of the

work of the IPCC, the data collection and scientific methods employed

are unsound. Resistance to all efforts to try and discuss or rectify

these problems has convinced me that normal scientific procedures are

not only rejected by the IPCC, but that this practice is endemic, and

was part of the organization from the very beginning. I therefore

consider that the IPCC is fundamentally corrupt. The only "reform"

I could envisage, would be its abolition....

Yes, we have to face

it. The whole process is a swindle. The IPCC from the beginning was

given the license to use whatever methods would be necessary to

provide "evidence" that carbon dioxide increases are

harming the climate, even if this involves manipulation of dubious

data and using peoples' opinions instead of science to "prove"

their case.

The disappearance of the IPCC in disgrace is not only desirable but inevitable....Sooner or later all of us will come to realize that this organization, and the thinking behind it, is phony. Unfortunately severe economic damage is likely to be done by its influence before that happens.

The disappearance of the IPCC in disgrace is not only desirable but inevitable....Sooner or later all of us will come to realize that this organization, and the thinking behind it, is phony. Unfortunately severe economic damage is likely to be done by its influence before that happens.

Patrick

Moore, a co-founder and director of Greenpeace, resigned

because of its “trend toward abandoning scientific objectivity in

favor of political agendas.” After the failure of communism, he

says, there was little public support for collectivist ideology. In

his view

a “reason environmental extremism emerged was because world

communism failed, the [Berlin] wall came down, and a lot of peaceniks

and political activists moved into the environmental movement

bringing their neo-Marxism with them and learned to use green

language in a very clever way to cloak agendas that actually have

more to do with anti-capitalism and anti-globalism than they do

anything with ecology or science.”

Vaclav

Klaus, former president of the Czech Republic and a university

professor before he became president, is the author of a book on

global warming and has spoken often on the subject. He says

, “What frustrates me is the feeling that everything has already

been said and published, that all rational argument has been used,

yet it does not help.”

It does not help because global warming alarmism is not based on rational argument. It is not based on science. It is not based on reality. It is based on political ideology. If rational argument doesn't fit, then phony arguments must be invented: the spread of malaria, the loss of biological diversity, oceans flooding, polar bears disappearing, Himalayan glaciers vanishing, etc. If global warming does not fit the observable temperature measurements, then a new “reality” must be invented to fit the ideology: actual temperature records must be altered or dismissed—hundreds of temperature-reporting stations in colder areas worldwide were eliminated from the global network so the average temperature is higher than when those stations were included link. Presto! Global warming. Ditto for carbon dioxide measurements: 90,000 CO2 measurements in 175 research papers were dismissed because they showed higher CO2 levels than desired, and various other studies were selectively edited to eliminate "uncooperative" measurements while claiming the cherry-picked remaining ones showed global warming (link.) The global warming advocates are not disturbed by all this because, in their view, ideology trumps reality!

It does not help because global warming alarmism is not based on rational argument. It is not based on science. It is not based on reality. It is based on political ideology. If rational argument doesn't fit, then phony arguments must be invented: the spread of malaria, the loss of biological diversity, oceans flooding, polar bears disappearing, Himalayan glaciers vanishing, etc. If global warming does not fit the observable temperature measurements, then a new “reality” must be invented to fit the ideology: actual temperature records must be altered or dismissed—hundreds of temperature-reporting stations in colder areas worldwide were eliminated from the global network so the average temperature is higher than when those stations were included link. Presto! Global warming. Ditto for carbon dioxide measurements: 90,000 CO2 measurements in 175 research papers were dismissed because they showed higher CO2 levels than desired, and various other studies were selectively edited to eliminate "uncooperative" measurements while claiming the cherry-picked remaining ones showed global warming (link.) The global warming advocates are not disturbed by all this because, in their view, ideology trumps reality!

Klaus

states (link link

link):

"We succeeded in getting rid of communism, but along with many

others, we erroneously assumed that attempts to suppress freedom, and

to centrally organize, mastermind, and control society and the

economy, were matters of the past, an almost-forgotten relic.

Unfortunately, those centralizing urges are still with us....

“Environmentalism

only pretends to deal with environmental protection. Behind their

people and nature friendly terminology, the adherents of

environmentalism make ambitious attempts to radically reorganize and

change the world, human society, our behavior and our values....They

don’t care about resources or poverty or pollution. They hate us,

the humans. They consider us dangerous and sinful creatures who must

be controlled by them. I used to live in a similar world called

communism. And I know it led to the worst environmental damage the

world has ever experienced....

“The followers of the environmentalist ideology, however, keep presenting us with various catastrophic scenarios with the intention of persuading us to implement their ideas. That is not only unfair but also extremely dangerous. Even more dangerous, in my view, is the quasi-scientific guise that their oft-refuted forecasts have taken on....Their recommendations would take us back to an era of statism and restricted freedom....The ideology will be different. Its essence will, nevertheless, be identical—the attractive, pathetic, at first sight noble idea that transcends the individual in the name of the common good, and the enormous self-confidence on the side of the proponents about their right to sacrifice the man and his freedom in order to make this idea reality.... We have to restart the discussion about the very nature of government and about the relationship between the individual and society....It is not about climatology. It is about freedom.”

“The followers of the environmentalist ideology, however, keep presenting us with various catastrophic scenarios with the intention of persuading us to implement their ideas. That is not only unfair but also extremely dangerous. Even more dangerous, in my view, is the quasi-scientific guise that their oft-refuted forecasts have taken on....Their recommendations would take us back to an era of statism and restricted freedom....The ideology will be different. Its essence will, nevertheless, be identical—the attractive, pathetic, at first sight noble idea that transcends the individual in the name of the common good, and the enormous self-confidence on the side of the proponents about their right to sacrifice the man and his freedom in order to make this idea reality.... We have to restart the discussion about the very nature of government and about the relationship between the individual and society....It is not about climatology. It is about freedom.”